Prohibition: Early Days

/Woodrow Wilson once told a story that: “In Maine before they had prohibition there was a great enterprise in manufacturing a brand of whiskey which made one intoxicated immediately. The best known brand that accomplished this was the one known as “squirrel whiskey.” A fellow in a local town after taking a drink or two of this squirrel whiskey developed a desire to travel. While this desire was uppermost a train pulled into the station, which he boarded. One of his friends missed him and discovered that he boarded the train. They immediately wired the conductor, describing him as a man who had just boarded the train, who was drunk, and who did not know where he was going. They asked the conductor to put him off and arrange to have him sent back on the next train. The conductor wired back: ‘Impossible; there are several men on this train so drunk that they can’t tell their names or their destination.’”

In the first decades of the eighteenth century, people in the United States drank more than a bottle and a half of hard liquor each week, far more than today. They recognized that drinking added to numerous social problems, and it came to be seen as an enemy to the moral rectitude of the American home. Temperance societies and religious groups fought to limit access to alcohol by the 1830s, but it was really after the Civil War that organizations concerned with other causes such as women’s rights and abolition turned their attention to what was known as the dry crusade.

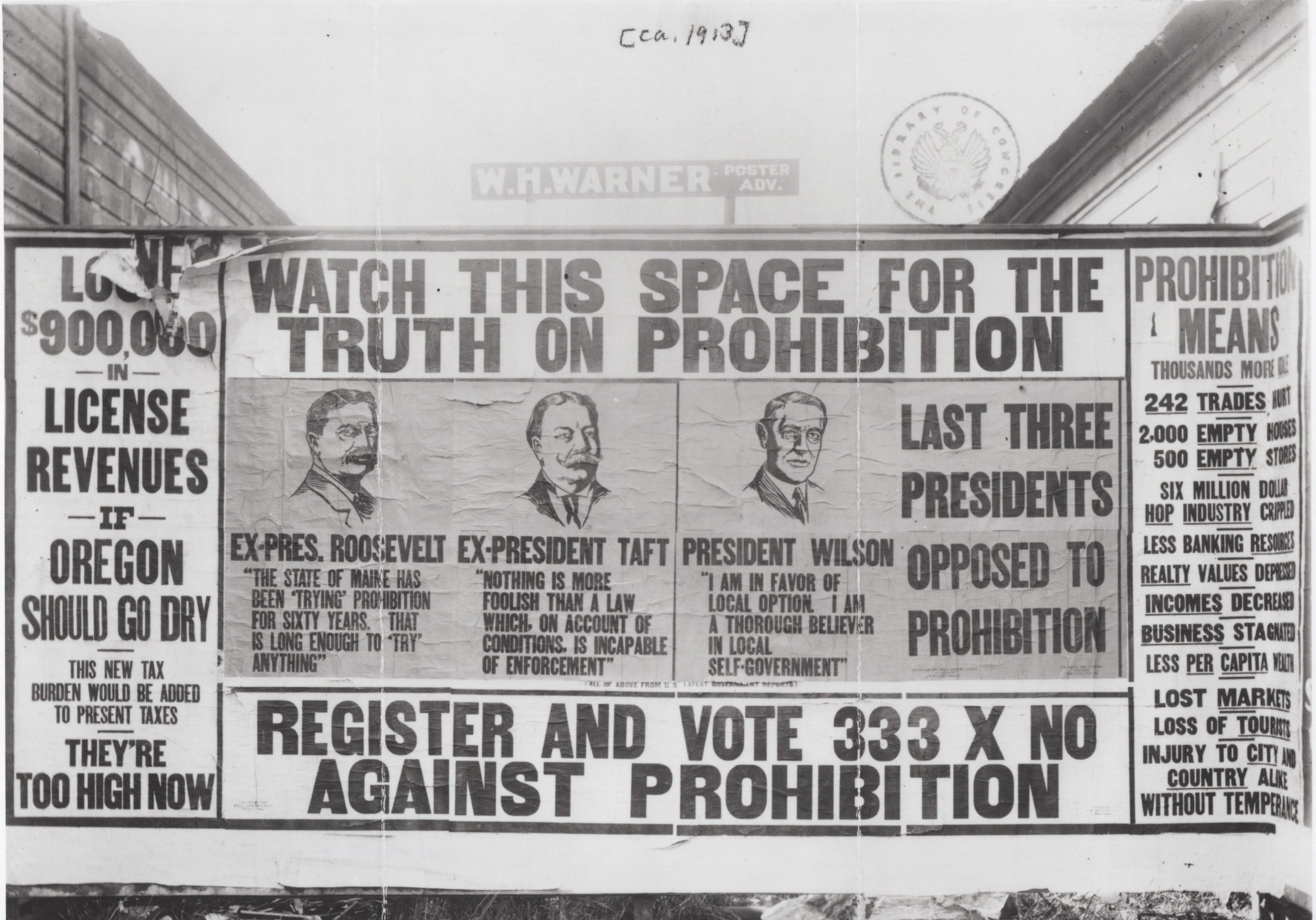

During the Progressive Era, temperance became a political issue. Not only did a wide swath of voters agree that there should be legal limits on access to alcohol, but it also proved to be a very effective single issue to campaign on in states that were otherwise equally divided. For his part, Woodrow Wilson largely agreed with the moral benefits of controlling liquor, but he felt that it was not a federal issue. The First World War, with its sweeping economic legislation, brought brewing and distilling under the umbrella of the president’s responsibilities. An Army bill of May 1917 stated that it was within the President’s power, “to make such regulations governing the prohibition of alcoholic liquors in or near military camps and to the officers and enlisted men of the Army as he may from time to time deem necessary.”

He remained loathe to step into the contentious politics of prohibition though. A 1918 report on brewing stated that, “the social habits and political prejudices associated with this trade are still so deep-rooted, though steadily weakening, that entire prohibition should be the result of deliberate legislation rather than of an administrative decree.” President Wilson agreed. He in fact kept his own cellar, and said, as Grayson recorded in his diary, “I notice in the papers that the States wanted to confiscate liquors and wines that have been stored in private residences … I think that is interfering with personal privileges.”

Further calls for the control of drinking by the troops and of the supplies that went into brewing brought about a general limit on the sale of alcohol for the entire country that actually was signed a week after the fighting stopped and came into effect a year later. 1919 also witnessed the passing of the eighteenth amendment and, with the Volstead Act passed despite a presidential veto, the rules to enforce the federal prohibition on the sale of alcohol in 1920.