Montgomery Hall

/In a recent blog post, the topic ended on the owners of the Montgomery Hall plantation in Staunton, one of the larger tracts near Staunton where enslaved people were forced to work the land. The Virginia Chronicle at the Library of Virginia offers some more information from the state’s newspapers on the fate of the house. For instance, we can see the sale of the land by John Peyton’s heirs shortly before Woodrow Wilson was born. Highlights included a vineyard of catawba grapes, acres already planted in wheat, and housing for enslaved farm workers.

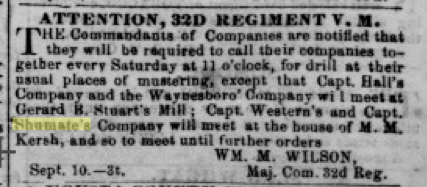

A curious article from before the Civil War about a visiting horse trainer confirms that the Shumate family had moved into the house. Otherwise, the articles from the years around the time that the Wilsons lived in the manse show Shumate losing a Newfoundland dog, bragging about the height of his corn, and serving on vigilance committees. In the Staunton Spectator for September 7, 1861, Shumate announces that he has wheat for sale. Then a week later a Captain Shumate of Staunton, though this might be Thomas Shumate, a relative, will have the men of his company meet at the house MM Kersh.

virginiachronicle, Library of Virginia

A later listing of the house for sale from 1869 gives some details about how the acreage had been divided. The house itself sat on 150 acres of land with orchards and cropland, right along the railroad.

virginiachronicle, Library of Virginia

The land appears to have remained for sale for four years until we find the Peck family living there ten years later. They held on to Montgomery Hall until 1902, but then the family of Frank Walter moved in shortly after that. Then the large mansion known as Montgomery Hall burned down in 1906.

Mrs. Walter’s father died a little over a year later at “beautiful Montgomery Hall” so it seems that the building was quickly rebuilt in a similar style. However, this long list of the owners of this opulent building is here for another purpose. As the age of Jim Crow stretched into the 20th century, Gypsy Hill Park near downtown Staunton was segregated and the land of the Montgomery Hall estate was used to create a specific park in town for African Americans near one of the poorer neighborhoods. As we see in a 1952 edition of The Tribune of Roanoke, “The Only Negro Newspaper Published in SW Virginia,” church groups often brought kids from all over Virginia to the park in Staunton, where they could enjoy the day unmolested.

Montgomery Hall in those days offered excellent facilities, but always with a clear understanding that they were put in place to enforce segregation on land that the fine mansion connected in obvious ways to the oppressions of earlier slavery. A video that was put together by the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library & Museum over ten years ago explains things a bit better, so let’s end with that. It is 18 minutes worth your time.

virginiachronicle, Library of Virginia