The Media Responds to a President

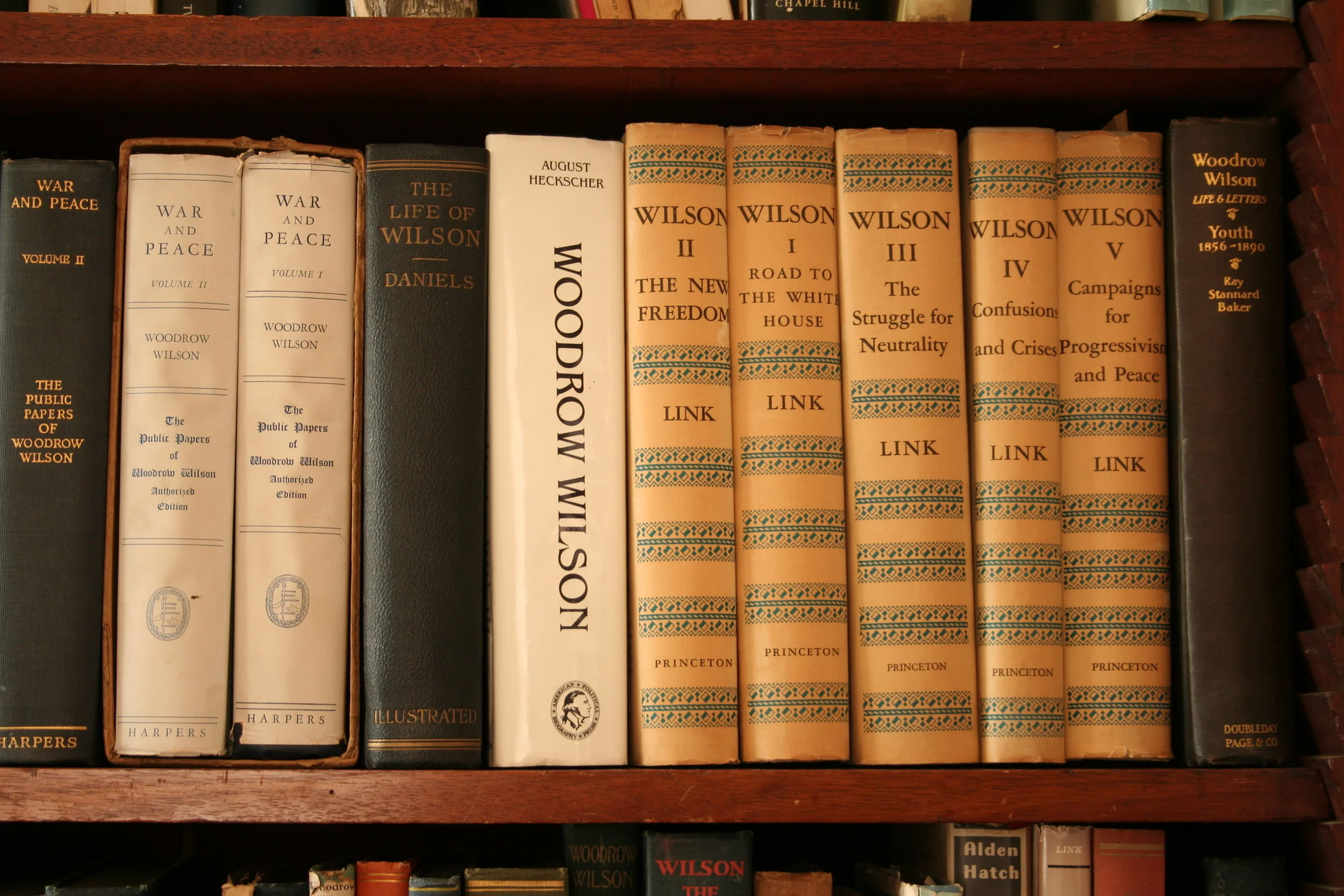

/In the first year of his presidency, Woodrow Wilson approved the imposition of segregation on several federal agencies that had not been racially divided up to that point, even in places where segregation had been common, such as Washington, DC. William Monroe Trotter, of the National Independent Political League, responded with a speech against the move.

We told you in person before election our fear of Southern sectional prejudice and asked you then, as a condition of advising African-Americans to support your candidacy, whether you as Chief Executive would protect us from its extension and you said you would. In what was tantamount to an agreement with these ten millions you wrote to your “Colored fellow citizens,” “It is my earnest wish to see justice done them in every matter, and not mere grudging justice, but justice executed with liberality and cordial good feeling.”

He called upon the president to remove the stain of segregation from his administration. To follow up, Trotter then pointed out a specific case of racial segregation to William C. Redfield, the Secretary of Commerce, and forwarded the text of his speech to Woodrow Wilson, writing, “With full confidence in your statement to the delegation that you would investigate. … May we have your response, and how soon?”

President Wilson never did respond. Any statements he made about segregation stressed his view that it was good for everyone, including African-Americans, and that this was not a political question to be decided by a president. The true force of his sentiments, however, could be seen in the government’s quick moves to expand segregation into other divisions in 1914, such as the discussion of plans for the Department of Agriculture.

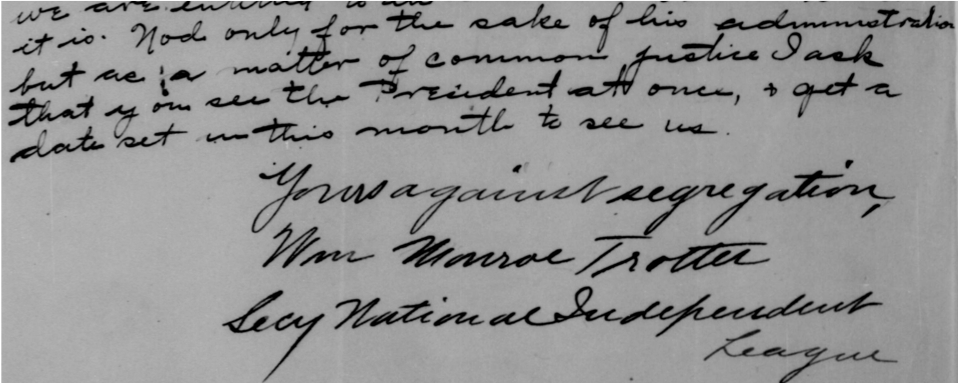

William Monroe Trotter to James A. Gallivan

William Trotter was outraged, as were many others. He joined a group of civil rights leaders in pressuring Wilson for a meeting on segregation.

As we have written elsewhere, the meeting did not go well. After listening to their petitions, President Wilson answered a few questions, and then grew outraged at Trotter’s attitude.

In the follow-up several newspapers opined that Trotter had brought further harm to race relations in the country. Racists denounced the black leaders for daring to call for equality. But there were also writers who supported the calls against segregation, and the “warm words” of Trotter’s anger.

Race Segregation

One critical article, apparently from the Boston Transcript, collected several pieces on the issue to show the deep ways in which the president had allowed his racism to deeply hurt his people, and his ideals.

The President holds that segregation under certain conditions is necessary to prevent racial friction between Government employees and that the reduction of friction means increased efficiency in the service. But something much deeper, much more fundamental is involved. If there are white employees who object to working within sight and sound of negro employees, they should be promptly confronted with the alternative of accepting such conditions of work or of leaving the service. For the so-called friction arises from a race prejudice which, in a large section of the republic, has been the underlying motive for a ceaseless assault upon the political and civic rights of the negroes under the constitution of the United States. The President declares that segregation is a human, not a political question. It is impossible to agree with him.

It ends with an article from the Hartford Courant, which brings the discussion back to the confrontation between Trotter and Wilson.

In his usual peremptory way, the President declared that it was not a political question, but Dr. Wilson's dictum may not be the last word. Anyway, the President was able to take refuge in the determination not to talk further with Mr. Trotter. Mr. Trotter will do his talking outside the White House.