Strikes

/Despite opposition, the United Mine Workers of America were able to organize among the workers of the Colorado Coalfields to the point that in 1913 they put together a list of miners’ demands, backed by the threat of a strike. Among other things, they insisted on an eight-hour work day, just like the UMWA had been able to win at other sites. Soon strikers were forced out of their company-owned housing and many moved to shanty towns in the area. There were threats of violence.

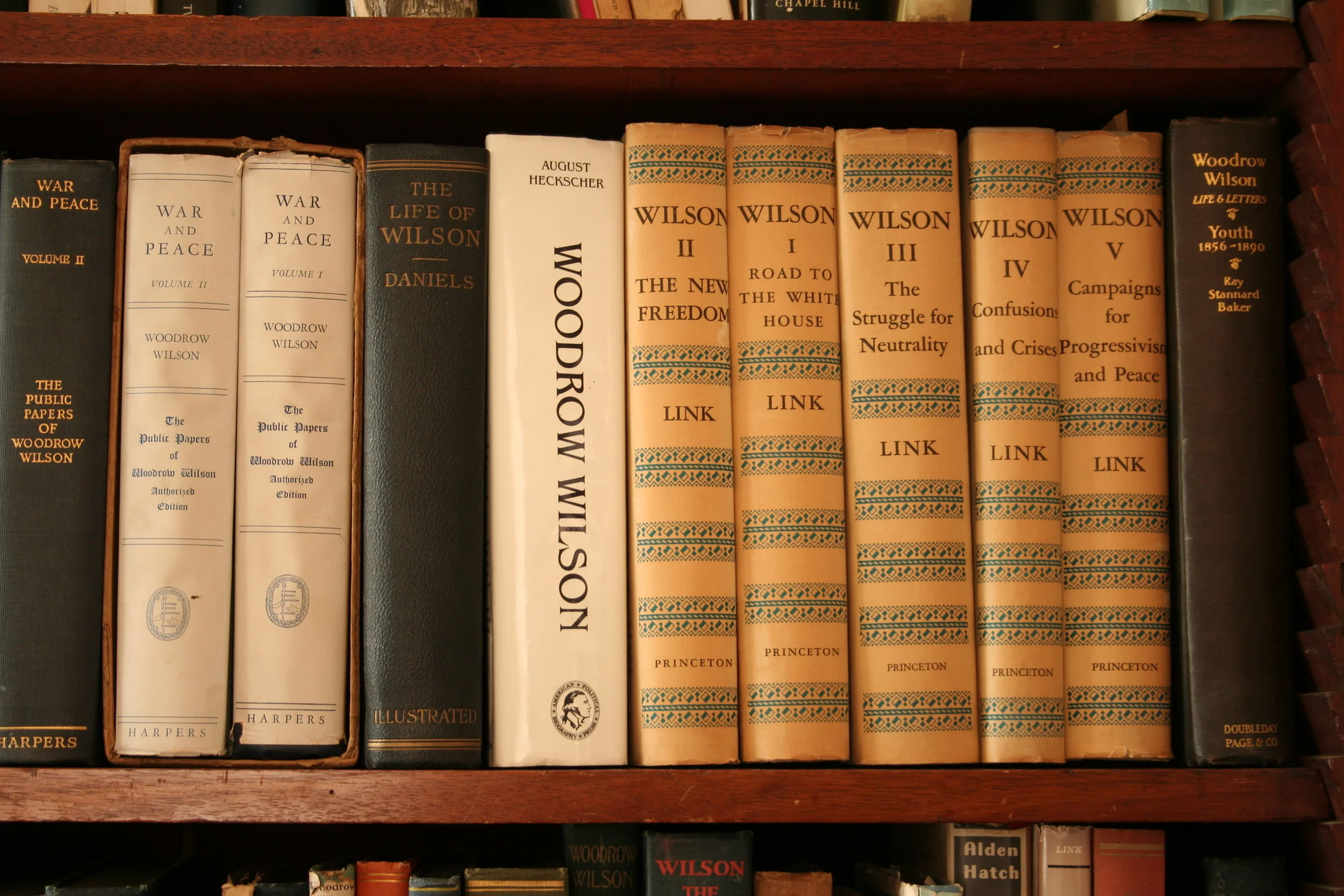

This was in the first year of Woodrow Wilson’s administration, and he put the federal government to work to bring about a resolution. The three big mining companies resisted the strikers’ demands, however, insisting that the union just wanted to meddle in their open shops. The government was unable to accomplish much, and the miners would give up after more than a year. Along the way, however, twenty-one people were killed at a small settlement in what came to be called the Ludlow Massacre, when Colorado State Militiamen attacked with a machine gun. In response to outrage at all of the violence, company owners, including JD Rockefeller, eventually imposed modest reforms after breaking the strike.

Organized labor had grown to become a powerful force in America during the first decade of the twentieth century. Though the country did not have workers’ parties like elsewhere, both Republicans and Democrats began to pay attention to ways that unions could get their members to vote together, and there were modest efforts to protect labor with new laws pushed by organizers and social activists.

Wilson put greater effort than earlier governments into helping workers, most notably with his appointment of William B. Wilson, who started his politcal career as a leader of the United Mine Workers of America, as Secretary of Labor.

The efforts of government, however, did little to ease many of the conflicts between the growing powers of large unions and massive industrial companies. Workers often turned to work stoppages to try to force improvements, to the point that strikes became a common tool of labor organizers. Teachers, streetcar operators, silk workers, and actors were just a few of the groups that held strikes in the period.

In 1919, over sixty thousand workers went on a general strike in Seattle over wartime wage controls. This particular event, however, proved to be the exception for the war years. Not only did many patriotic workers, and companies, pledge to overcome any differences in the interest of maintaining the country’s war efforts, but Wilson could compel groups to arbitrate conflicts quickly in important industries as part of his war powers. Perhaps more importantly, the organization and investment put into war provided higher wages and profits for many Americans, so that there was less labor unrest in the next decade.