That Veto

/On September 25, 1919, in the town of Pueblo, Colorado, President Woodrow Wilson stepped down from his private railcar to give a speech. He was to be the first person ever to address the townspeople in the new City Auditorium. Wilson explained the importance of the League of Nations for the numerous peace agreements that ended the war for the United States, and he showed the ways in which the League would prevent further battles for American soldiers. Not only would it allow conflicts to cool off, before they led the parties to declare war, but also show the common consensus of the world.

The most certain way that you can prove that a man is mistaken is by letting all his neighbors know what he thinks, by letting all his neighbors discuss what he thinks, and, if he is in the wrong, you will notice that he will stay at home, he will not walk on the streets. He will be afraid of the eyes of his neighbors. He will be afraid of their judgment of his character. He will know that his cause is lost unless he can sustain it by the arguments of right and of justice.

Wilson ended his speech with a rousing call for suppport:

There is one thing that the American people always rise to and extend their hand to, and that is the truth of justice and of liberty and of peace. We have accepted that truth, and we are going to be led by it, and it is going to lead us[.]

That evening he would suffer what appears to have been a small stroke, which would be followed by a more significant stroke on October 2, and then further health complications which in all would put his presidency at risk. In many ways he was never the same man again. We have written about this event before, but I want to return to it here, because of Prohibition.

Recently, we had a film crew here in the archive preparing a documentary on Wilson and his health. They were mostly interested in hearing about what happened to the President when he was resting for those many months after his stroke. Everyone wants to know. Apparently there are even some movies being optioned on the topic right now.

Much of what people did in Wilson’s inner circle at the time remains a mystery. But there might be a few clues if we look at the text of the formal announcement of President Wilson’s October 27 veto of the Volstead Act.

One part of the act under consideration seeks to enforce war-time prohibition. The other provides for the enforcement which was made necessary by the adoption of the Constitutional Amendment. I object to and cannot approve that part of this legislation with reference to war-time prohibition.

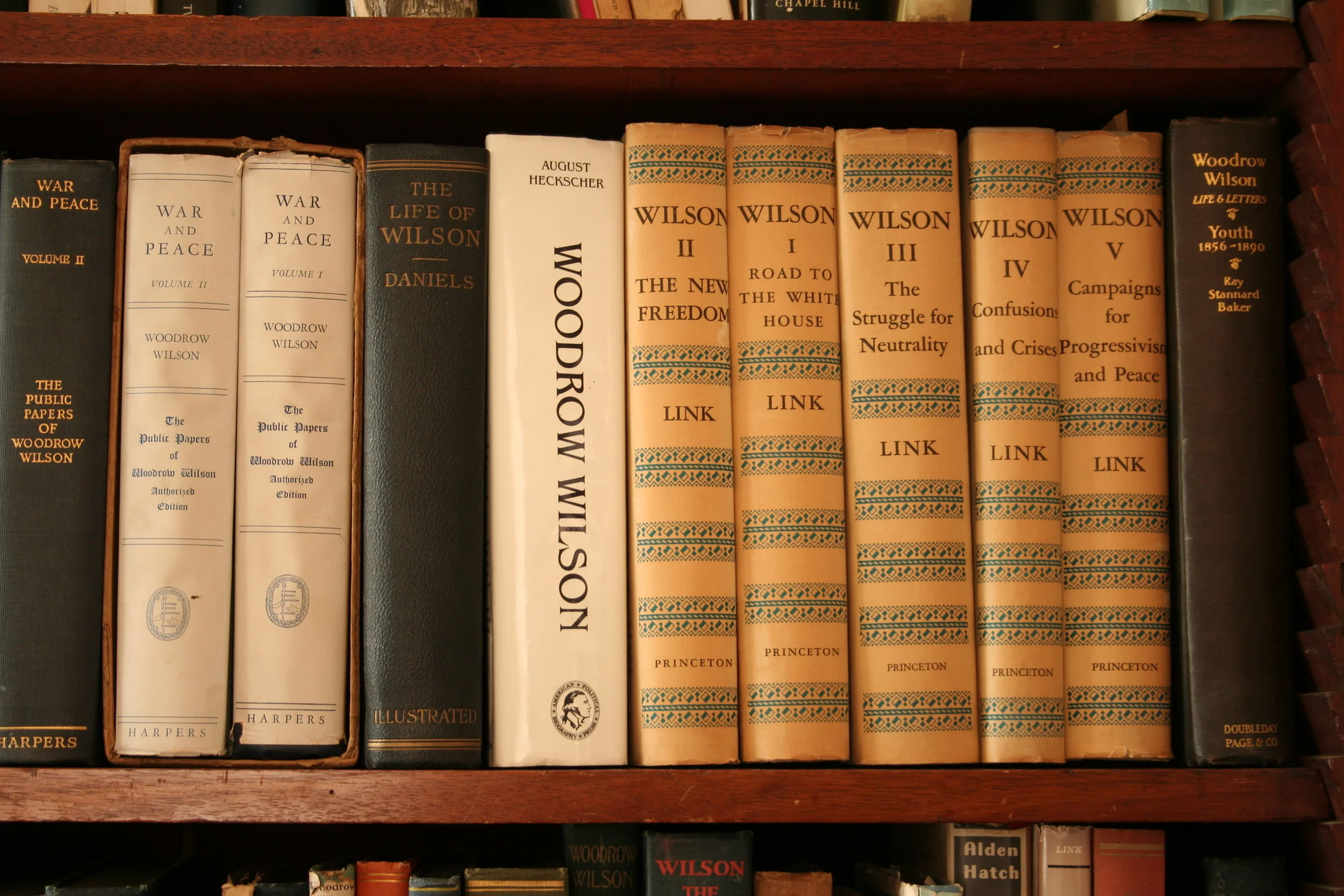

He expected Congress to separate the two issues to successfully enforce the 18th Amendment from January of that year. This is a strong statement from someone who has been in bed for a month. And it deals with issues that were of a type that concerned Wilson. The neurologist’s revised report from the time suggests that the doctor had observed marked improvement in an examination of President Wilson on October 18. But still, Dr. Grayson wrote to Ray Stannard Baker on November 1, “I read the article to Mrs. Wilson and she was very highly pleased with it. I also told the President the substance of it” and then goes on to say that the, “President continues to mend slowly. It is a long hard pull but I am hoping for the best.” Wilson’s mind does not seem to have been of great concern, but this does not sound like someone looking to pick a fight with Congress.

It is important to note that much of the mail received on the topic of Prohibition that October included calls for a veto.

Nor should we forget that Joseph P. Tumulty, Wilson’s secretary, knew very well how where he stood on issues like this, and how he would probably respond. Prohibition had been in the air for years. President Wilson only vetoed thirty-three bills during his administration. Two of them were in November of 1919, when he also issued a Thanksgiving proclamation, though apparently few letters.

On the seventh of that month, Senator Hitchcock barged in for an interview at the White House. Grayson quotes Wilson as saying, “I have been lying on my back and have been very weak, and it has fatigued me to read and to discuss matters in my mind, so to speak. I have been kept in the dark to a certain extent except what Mrs. Wilson and Doctor Grayson have told me, and they have purposely kept a good deal from me.”

As time went on, and Wilson continued to rest, people would become more alarmed at the state of his health. For that October, however, it seems that the veto does not prove all that much, and, of course, not signing the bill means that there is no shaky signature to compare to any of his others. All that we can say is that Wilson probably had the wherewithal to state his views on the legislation, views he had expressed before that year, and his secretary, wife, and doctor were in a position to shape the document that announced his decision, fighting back any efforts to learn the full truth and any calls to remove him from power.