Meditation on a Term

/Recent scholarship has stressed how much “Anglo-Saxon” is really more of a modern term than a reflection of medieval identity. Contemporary documents from the Early Middle Ages rarely mention that name, but as scholars of English became focused on the idea of an old, original language in the sixteenth century, they called it Anglo-Saxon after two Germanic tribes. Late in the 19th century, just as historians began to link the laws of these groups to the liberties of both England and the America, scholars again discussed the idea of the ancient Anglo-Saxons. Numerous dictionaries and documents were produced for a wide market of educated people to study the origins of English language.

Comparison of use, from 1850-1920, of the term Anglo-Saxon versus Mercian, an old kingdom.

Today the term is familiar, but any look at the 19th-century scholarship makes it clear that many of the intellectuals discussing Germanic tribes had clear racist agendas to show the Anglo-Saxons to be superior to the Irish, immigrants, or African Americans. Popular speech picked up on this. Even when people used the term playfully to set themselves apart from Germans or Swedes, Irish-Americans or Jewish-Americans, claims of superiority do not seem to be far away. Some ask whether current scholars should be more exact in who they refer to, while also unshackling their work from hatreds of the past, by giving up on the name Anglo-Saxon.

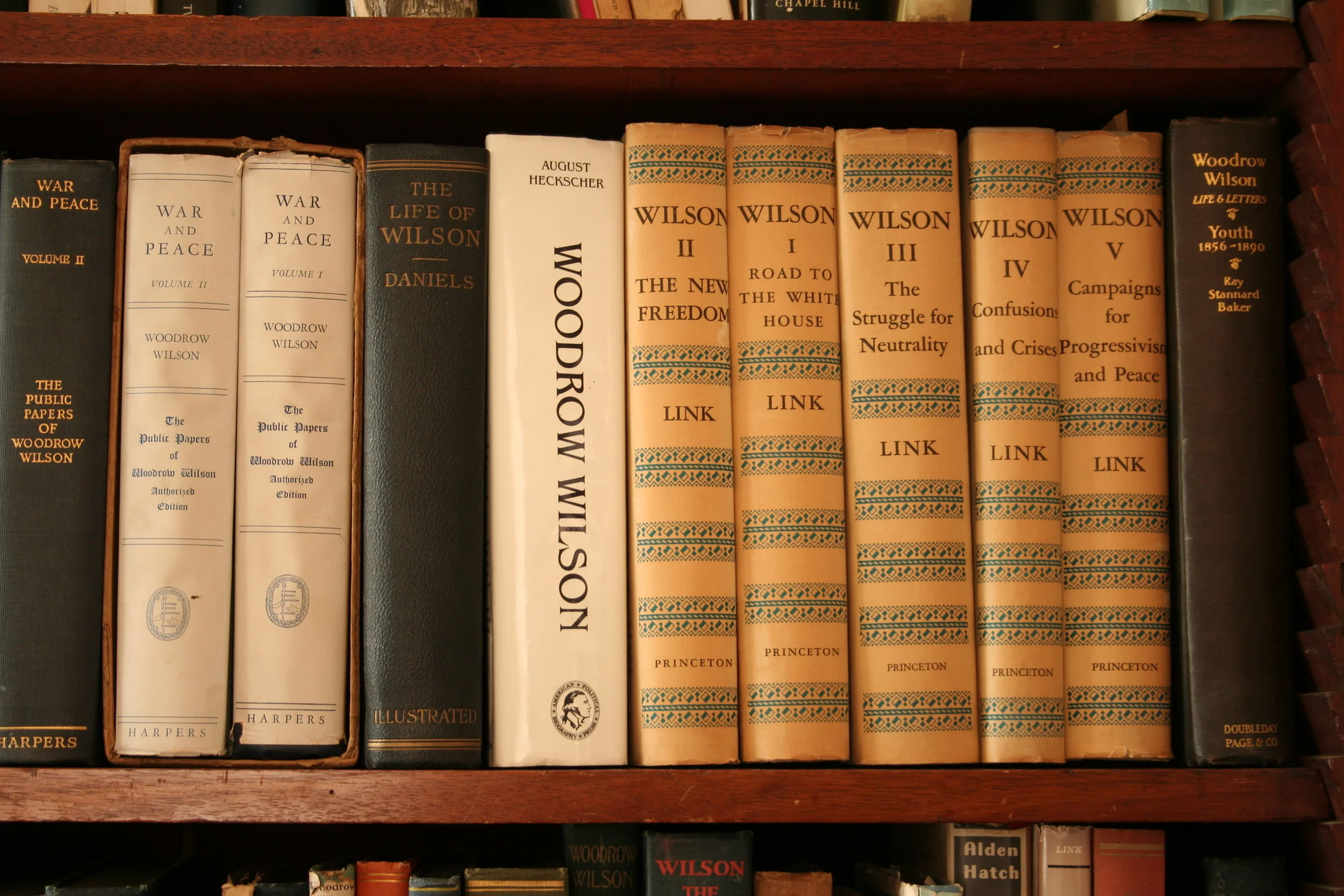

The career of Woodrow Wilson shows the complexity of this issue when we really look at how people understood what it meant during his lifetime. As an academic, Wilson knew all about the Anglo-Saxon scholarship. From his earliest days as a student at Princeton, he studied English in a two-year class with Theodore W. Hunt, one of the most prominent American linguists to stress the importance of understanding the original language. According to the Princeton catalog of 1875, the coursework included the, “origin of language, study of language, the place of Anglo-Saxon in the family of languages.” In one of his own history essays, Wilson wrote in 1879 of “institutions which our Anglo-Saxon race looks upon as peculiarly its own.”

A 16th Century Fake Biography of Alfred the Great at Johns Hopkins Original manuscript lost.

Wilson’s history professor at Johns Hopkins University, Herbert Baxter Adams, was a proponent of tracing the traditions of New England democracy back to the Anglo-Saxons. As a teacher, Woodrow Wilson would regularly cover the Germanic invasions of Britain as a class topic and refer to the tribes in his work, such as when he wrote in 1893, “The American spirit is something more than the old, the immemorial Saxon spirit of liberty from which it sprang.”

Wilson was also very conversant in the more common uses of the name, though he often just used “Saxon.” Like many American Presbyterians, he traced his heritage back to the Scots-Irish, who had settled in Northern Ireland. That might explain why he was often quick to point out his affinity for the Anglo-Saxon, hence Protestant, heritage. He wrote to his wife in 1886 that Mr. Aldrich of Boston had “good Saxon coloring.” On his bike trips in England, he frequently notes the Saxon elements visible in the towns. When giving a speech on the anniversary of the King James translation of the Bible, Wilson focused on literature and heritage.

There is more of the spirit of our own institutions in a few lines of Tennyson than in all the textbooks on governments put together: Can you find summed up the manly, self-helping spirit of Saxon liberty anywhere better than in those few lines?

None of this is to deny that Woodrow Wilson was familiar with uglier claims about Anglo-Saxon heritage. Home from law school at the University of Virginia in 1881, he had started a letter in response to a request from the Philadelphia American to hear from thinkers of the South. Editors, however, had warned Wilson that his initial drafts provided ammunition for northern Republicans when he wrote that the politics of the “Saxon race of the South” would always be dominated by that group’s determination to never again allow African Americans to have the chance to influence democratic institutions. They considered that an insult to their sense of Anglo-Saxon superiority, he wrote. In the end, his letter on the New South was published in the New York Evening Post on April 26, 1882. Wilson had removed all reference to what he had previously said was the chief concern of Southern politics to instead focus on the importance of family pride and the need for capital. Statements connecting Anglo-Saxon identity and American racism proved to be too controversial.